The history of the human race has shown that a majority of approaches to human welfare have been based on the views, experiences and needs of the dominant classes. The expressions and cultures that are considered to be the norm are based on unequal power relations and structural differences influenced and perpetuated by the dominant classes. In such a situation, it is easy to label differing opinions, expressions and cultures as deviant or inferior on account of the asymmetrical knowledge production that exists in society. It is therefore, imperative to delve into a critical analysis of what we accept as the ‘normal’ in light of the discussions regarding the indigenous tribe of the Jarawas in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The history of the human race has shown that a majority of approaches to human welfare have been based on the views, experiences and needs of the dominant classes. The expressions and cultures that are considered to be the norm are based on unequal power relations and structural differences influenced and perpetuated by the dominant classes. In such a situation, it is easy to label differing opinions, expressions and cultures as deviant or inferior on account of the asymmetrical knowledge production that exists in society. It is therefore, imperative to delve into a critical analysis of what we accept as the ‘normal’ in light of the discussions regarding the indigenous tribe of the Jarawas in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

History of the Jarawa

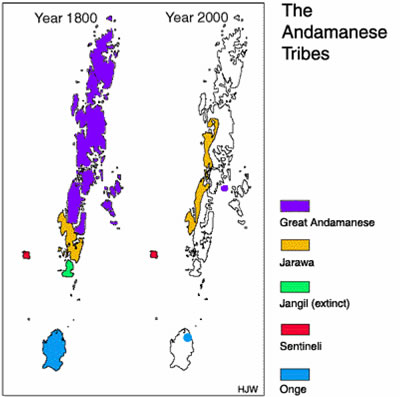

The Jarawas are considered to be the last existing Palaeolithic tribe in India which allegedly migrated from the African subcontinent around 55,000 years ago and are currently settled in the middle and south Andaman islands in a 1,021 km Jarawa tribal reserve,[i] set up by the Indian government under the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (ANPATR) in 1956. The Jarawas are a self–sufficient community of hunter-gatherers, who had completely excluded themselves from any form of cultural or social interaction beyond their tribe.[ii]

In the early parts of the colonial era, the British tried to inhabit the islands and forge friendly ties with the indigenous tribes by setting up ‘Andamanese Homes’ and provided them with ration, shelter, etc. While the colonizers managed to pacify the other tribes like the Onge and the Great Andamanese, [iii] the Jarawas remained hostile towards any kind of contact made by the outsiders, colloquially known as the enen.[iv] This led to the British setting up ‘Bush-Police Outposts’ around the Jarawa territory in order to reduce the conflict and protect the tribe. However, with time, these patrols started exploiting the Jarawas as well as the resources within the reserve.[v]

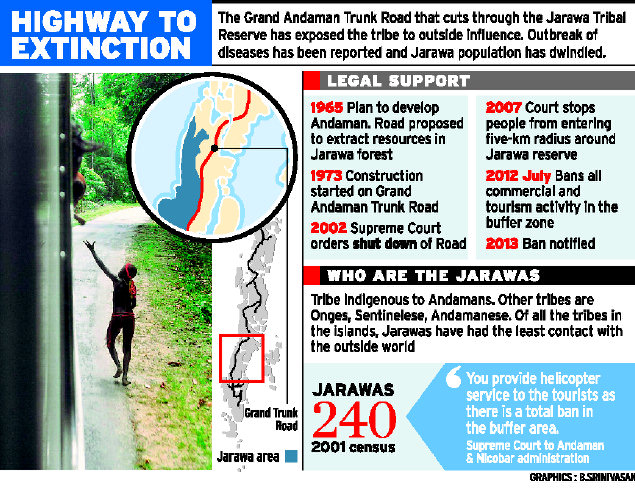

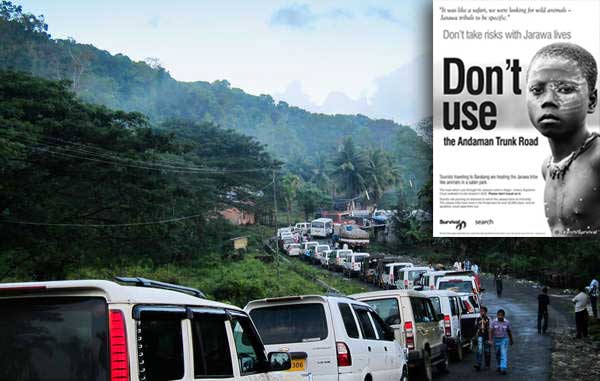

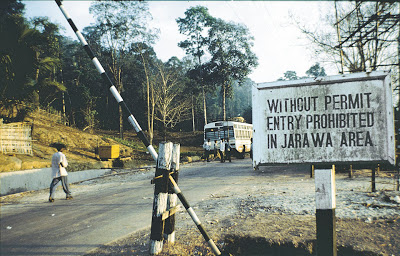

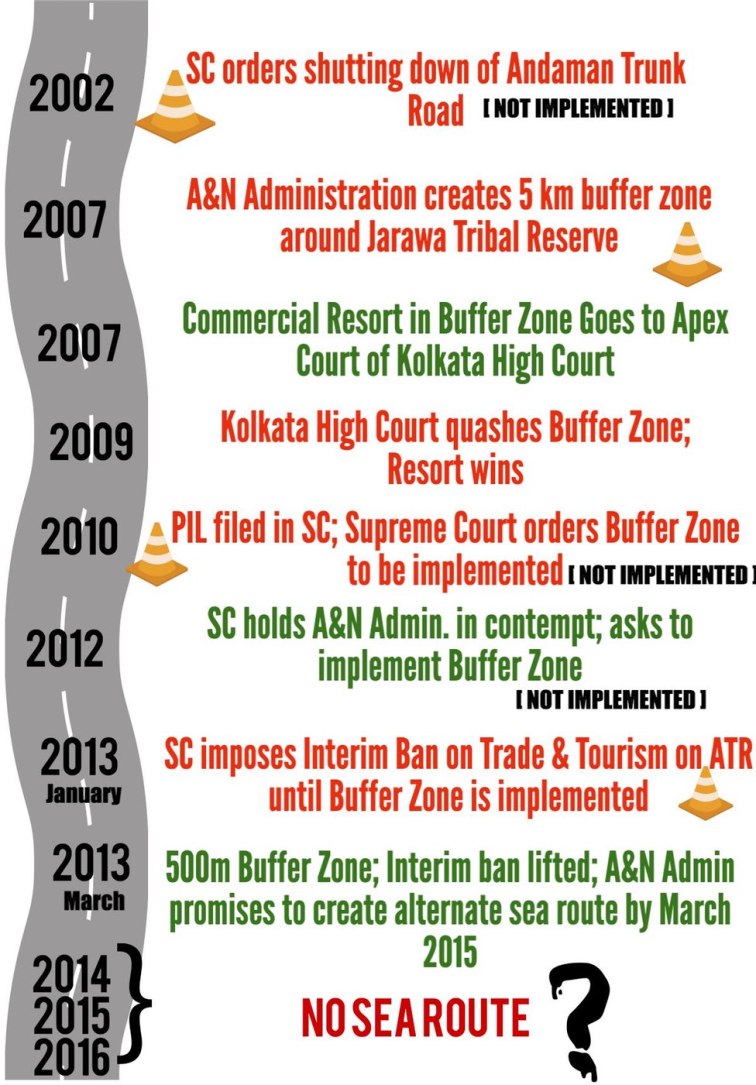

In the post-colonial era, due to an increase in the number of people inhabiting the island, a need for development of infrastructure was felt. One of the outcomes of this was the construction of a 343 km ‘Andaman Trunk Road’ also known as the ATR, 35 km of which cut through the Jarawa reserve. The Jarawas initially responded to the construction by attacking the labourers, obstructing the traffic and attacking vehicles. However, the construction of the ATR eventually led to an increased interaction between the Jarawas and the non-Jarawas settled in and around the reserve. This has in turn exposed this vulnerable tribe to the threat of disease, sexual exploitation, human rights abuse and discrimination within their own lands.[vi]

The Jarawas in the Media

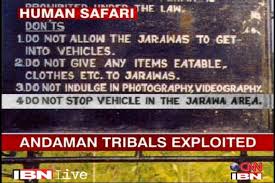

In 2012, a British journalist Gethin Chamberlain working with the Guardian Media Group brought to the notice of the world a few videos where the tour operators and government officials were using the Jarawa women to film advertisements for ‘Human Safaris’ where the Jarawas had been portrayed as tourist attractions. In the videos, a group of semi-naked Jarawa women were being made to dance on the instructions of the government officials while the tourists watching them in amusement, threw food and money at the Jarawas.[vii]

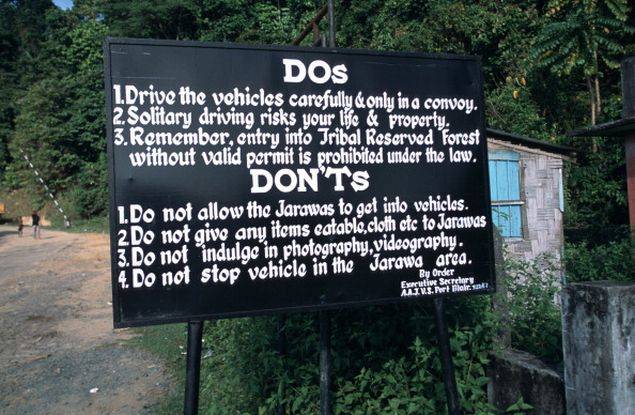

These acts of the officials were in serious contravention of the Protection of the Aboriginal Tribes Regulation, 1956 which makes any attempt to contact the tribe, photograph them, stopping vehicles within the Jarawa reserve etc. punishable offences.[viii] The videos generated large scale debate among various sections of the society that were not limited to only discussions regarding the vulnerability of the tribe, issues regarding their privacy, oppression and marginalisation but also extended into racist comments and trolling on social media. This makes it imperative for us to look into this exploitation of the Jarawas and the shift from ecotourism to human safaris. It must be noted however, that the 2012 videos only gave us a glimpse of larger problems that the Jarawa tribe has faced since its accelerated contact with modernity in their own land.

The videos released in 2012 showcased the abusive attitude of the officials, tour operators and the tourists towards the indigenous tribe of the Jarawas. In addition to this practice of ‘Human Safaris’, the enen have been indulging in a host of other exploitative acts against the Jarawas. There has been encroachment not only in the buffer area surrounding the reserve in the quest for resources but also deep within the reserve itself. It is pertinent to note that some of these encroachments, in violation of the policies in place, have been committed by the Bush police and the government officials.[ix] There have been various instances of trafficking of the members of the tribe by the enen, where the police and other security personnel have chosen to ignore the injustices done unto the tribe and have themselves been complicit in these acts.[x] The enen have also set up liquor, tobacco and marijuana (substances that have been unknown to the Jarawa culture) shacks around the Jarawa forest reserve, in addition to this, obscene movies are also screened in these shacks in order to coax the indigenes to indulge in sexual acts.[xi]

Analysing the Reportage of the Jarawa in the Media

The videos using the Jarawa women in order to advertise the ‘human safaris’ among the tourists brought forward a larger debate in the media about the tussle between a universalist idea of social progress and the protection of the indigenous culture of the Jarawas. The Jarawa issue in the media can be analysed through two different lenses. The first being the idea that the State should set up a policy that leads the Jarawa towards mainstream assimilation by providing them modern tools of survival ultimately leading to their integration into the developed world. Reports supporting inclusion rely on the argument of deprivation of the benefits of municipal recognition, civil rights, modern scientific education and economic progress that cannot be accessed by the Jarawa if they choose social exclusion.[xii] Anthropologists like G.S. Ghurya argue that the State authorities and institutions provide the way forward for indigenous gated communities like the Jarawa to survive and assert that the lack of socio-political rights and the deprivation of the fruits of modernity are tantamount to a denial of humanity.[xiii]

The counter discourse has been in contravention with these ideas of assimilating the Jarawas into the mainstream culture where the degree of social integration and assimilation is dictated by persons and institutions other than the Jarawas themselves. This idea aiming to protect the indigenous culture of the tribe proposes that the Jarawas should have the freedom to determine the pace of their social progress without being subject to external standards imposed by the ideas of the dominant mainstream. This argument has been aptly summed up by the editor of the Andaman Chronicle, Denis Giles in the following statement,

“I believe that one fine day the Jarawa will have to come out and mix. They can’t stay in the forest for ever. They are aware that there is a world outside the forest. But it should not be a cultural shock to them; they should choose the pace at which they do it.”[xiv]

The discourse in the media regarding the protection of the indigenous rights of the Jarawas believes that forced assimilation could lead the Jarawas to the brink of extinction[xv] due to powerful forces and structural barriers of the mainstream society.[xvi] The head of the Anthropological Survey of India, Dr. A. Justine remarked that “forced coexistence would be a total genocide for the Jarawas.”[xvii] These tribes are vulnerable to a host of unfamiliar diseases and any amount of forced interaction with the outside world could lead to their total extinction. Something similar happened to the Great Andamanese, another indigenous tribal group who were in considerable contact with the outside world which led to the outbreak of disease within the tribe and their numbers dwindled from around 10,000 to just under around 50 at present.[xviii] Adverse inclusion,[xix] the lack of social capital and uprooting of socio-economic lifestyles has in the past led to the abject marginalisation and resource deprivation of indigenous people when exposed to the forces of assimilation.[xx]

While the media coverage captures these dichotomous schools of thought that underpin the policies toward the Jarawas, another aspect of the reporting is the inaction of the island authorities in the implementation of the policies in place.

In spite of regulatory measures, welfare programmes and institutions set up for the protection of the Jarawa, reports strongly suggest inadequacy of implementation of these safeguards by the local administrative bodies. The Jarawa continue to bear the brunt of exploitation even though the ANPATR 1956, the Jarawa Tribal Policy (2004) and other legal safeguards are in place. The failure of the safeguards is attributed to the inefficiency of the three island authorities – the Andaman Aadi Janjati Vikas Samiti (AAJVS), the Bush Police and the Forest department. These agencies are required to work in tandem to prevent conflicts, unintended external contact, exploitation of natural resources and illegal poaching to ensure the overall welfare and protect the vulnerable island tribes.[xxi] However, reports point to the lack of sensitization, apathy, corruption and the lack of coordination between these agencies as the reasons for the inefficiency in implementation of tribal policies.[xxii] Instances of official laxity were vociferously reported after the publication of the sensitive videos in 2012 when an inspector general of police specially deputed to monitor the activities on the reserve was transferred after it was reported that he took his family members on a human safari.[xxiii]Another case of administrative failure was when it came to light that three French filmmakers had been infiltrating the reserve continuously for a few years and were about to publish a documentary, We are Humanity, after having interacted directly with the Jarawa with the island administration remaining clueless about their presence.[xxiv]

Strong national and international pressure, publications and reporting by individual campaigners and organisations like Survival International and Kalpavriksh have exposed the negligence of the Andaman administration in implementing the Jarawa policies on multiple occasions.[xxv] While various administrative agencies have issued notifications and filed affidavits for the implementation of the ANPATR and the Jarawa Tribal Policy,[xxvi] accounts of reporters and activists show negligible change in actual implementation, often due to vested interests of technocratic lobbies.[xxvii] More recently, the reportage vehemently opposed the Supreme Court order in March 2013 that lifted the ban on commercial and tourist activities within the Reserve and in the Buffer Zone, [xxviii] contradicting a string of judicial victories for Jarawa campaigners in 2002, 2012 and January 2013.[xxix]

Conclusion

The analysis of the reportage of the Jarawas in mainstream media has seen the campaign for the indigenous assertion of culture and progress of the Jarawas gain political traction. The counter discourse that encourages the Jarawa to decide the pace of their development and degree of contact with the outside world has thus, changed the tide of public opinion, largely due to the efforts of campaigners and activist organisations. Previously, the tribe survived in its self-contained world free from any outside contact, however, this increased contact has exposed the tribe to a risk of disease, scarcity of resources and exploitation, pushing the tribe to adapt to a way of life that they might not have chosen for themselves.[xxx] Sophie Grig of Survival International highlights the importance of not pigeon-holing the tribes as primitive or beastly simply on account of them following a way of life that does not conform to the modern ideas of living.[xxxi]

The laying of the Andaman Trunk Road through core areas of the Jarawa reserve, the limiting exercise of confining the Andamanese tribes to certain tracts of land by the enactment of the ANPATR, 1956 and other acts of marginalisation indicate the deep seated structural norms of social organisation and development that the State authorities have adopted so far. Conversely, it has also exposed the deep hypocrisy of these governmental policies and the absence of their implementation by the local island authorities, who have often been perpetrators of offences against the indigenes.[xxxii] In light of these structural barriers, there is still an uphill task for these groups and the Jarawas themselves of being recognised in appropriate forums to bring about institutional change that have so far, been few and far between. While there may be a rising opposition to the government’s policy of assimilation, institutional changes that are sensitive to the protection of the cultural heritage and peculiarities of the Jarawa remain lacking in several respects. There is a need to address sensitive issues like environmental concerns, recognition of Jarawa cultures and perspectives in political decision making, rethinking modes of development on the Andaman Islands and the management of the Jarawa Tribal Reserve on a priority basis in order to truly secure a better future for India’s oldest Palaeolithic tribe.